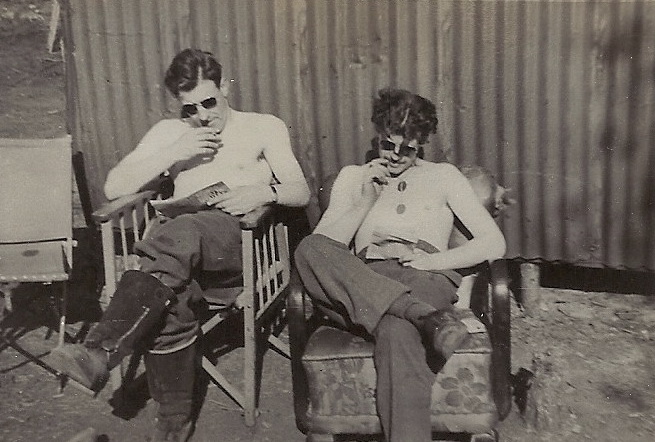

F/O John Kilgour “Paddy” Byrne

197 Squadron pilot John Kilgour “Paddy” Byrne was posted to 197 Squadron at Tangmere in March 1944 and served continually with the Squadron for sixteen months. During that period he was stationed on sixteen airfields and had four commanding officers and six flight commanders. He flew convoys and other defensive patrols plus 150 offensive sorties, had two official 48-hour passes and seven days of leave. Here he shared some memories and logbook entries.

Whilst in Tangmere, like all new boys, I flew convoy patrols and sat at the end of the runway as a No. 2 at cockpit readiness (strapped in, helmet, goggles, oxygen on and ready for take-off) hopefully to intercept the hit-and-run raiders on the South coast. On the 10th of April, we gave up the amenities of Tangmere, a pre-war RAF station (comfortable mess, waitress service, twin-bedded room, hot and cold running water), for a large field at Needs Oar Point. There we lived, ate and slept in tents. We washed occasionally in a bucket of cold water, with a hole in the ground toilet, and stood in line with a tin plate for dinner. Little did I know that this would be our way of life until the war ended.

1st offensive op. (OV-P)

Dive bombing the airfield at Abbeville crossed the Channel at wave-top height, climbed to 7,000 ft. to cross the French coast, dropped the bombs and returned to England. The ground crew told me that I had been hit by flak, although the other pilots reported flak over the target, I did not appreciate that the black puffs of smoke were dangerous.

2nd op. (OV-K)

Dive bomb radar site at Fruges. The engine started to cough as I climbed up after the attack. The CO said “head for England” and assisted by crossed fingers, sweaty palms and intermittent engine coughs, landed on the emergency strip at Beachy Head.

3rd op. (OV-R)

Divebomb Nobal (flying bomb site), Helsdin. Hit by flak again – hydraulics u/s, no flaps, no undercarriage. Flying control at Needs Oar Point instructed me to land wheels up at Beaulieu. The airfield appeared to be deserted; two low passes of the control tower evoked no response so I put OV-R on the grass. As we skidded to a stop I was out and fifty yards away in a matter of seconds. It was still very quiet and then suddenly all hell broke loose: rockets flew into the sky, sirens wailed, bells rang and the U.S. cavalry arrived. The aircraft was covered in foam, I was bundled into the “Bloodtub” (ambulance) and rushed to the sick bay. Although I protested that I was alright, they gave me a medical. I was then debriefed and I had to smile when the Major said, “Gee Colonel, can you believe it? A God-darned Tech Sergeant flying a Pursuit Bombardment Ship on a mission.”

4th op. (OV-D)

Ramrod. Hit again by flak on tailplane.

Something told me that I was pursuing a very dangerous occupation and I contemplated a transfer to the Commandos or the Paras, but the thought of all that marching, sharp knives and blood put me off. When the Squadron was stood down, the CO authorised practice flights. These consisted of dog fighting, tail chasing and acrobatics. The CO – “Butch” Taylor – always led these flights and if any pilot did not meet his standards, they were sent back to Aston Down or OTU.

At the end of May, we realised that the invasion was near. The Solent was choc-a-block with ships, and the New Forest was full of tanks, guns, trucks and troops. On the 5th of June, Ramrod (OV-D) attacked an RDF site and in the afternoon did an unsuccessful air-sea rescue patrol (OV-D) to look for Sqdn Ldr Ross of 193 Sqdn who had gone into the drink. That evening, all pilots had to report to the briefing tent where Group Captain Gillam announced; “Tomorrow is D-Day”. Winco Flying (Reg Baker) said the Wing would provide Cab Rank patrols over the beachhead from dawn to dusk. Not many people slept that night. The planes were re-armed and refuelled, had their engines tested and were painted with black and white identification stripes. First patrols were off at dawn. My turn came in the afternoon, the entry in my log book reads: “OV-Z D-Day, armed recce Caen area. Bombed German camp, shot up trucks and Jerry soldiers. Flying time one hour and twenty minutes.”

Life was pretty hectic for the next three months; the Squadron flew every day – weather permitting. Some days, pilots could do three or four sorties. When airstrips became available in Normandy, we would take off from England, attack the target, land in France at B15, re-fuel, re-arm, do another sortie and return to Needs Oar Point. On one such trip, when we landed in France we were told that we could not return to England because the weather had clamped down at Needs Oar Point. I knew one of the servicing commandos (we had been aircraft apprentices together at Halton pre-war) and asked where they spent the night. He said that there were no facilities on the strip and as the Germans also shelled it, they went back to their camp. I suggested to the CO (Butch) that we should join them but oh no! It was our duty to stay with the aircraft. What four pilots armed with revolvers could do against 88 mm shells was beyond my comprehension. When the first shell arrived around three in the morning, we took refuge in a slit trench where the conversation was rather subdued. Luckily there were only a few shells and they all fell at the far end of the field.

After a short spell at Hurn, the Squadron moved to B3 in France. Normandy was hot and dusty, making life difficult for the ground crews as the dust was like fine sand and caused terrible problems with the aircraft. Engines suffered from excessive wear, fuel had to be filtered, hydraulics failed and all servicing was done in the open with minimum equipment. We were now dependent on our own resources. At Needs Oar Point we could go to the local pub for a drink or a meal and, with a bit of luck, have a bath and arrange for someone to do your laundry. Not anymore; we washed our clothes occasionally in a can of boiling water and lived on Compo rations until bread and potatoes became available. Contact with the local population was limited, mainly to the purchase of cheese and eggs from nearby farms. Entertainment was a display of fireworks every night when a lone Jerry Recce aircraft flew over the beachhead. Although he was coned by searchlights and fired at by hundreds of “ack ack” guns, they never shot it down. German ack ack would have got it first time!

Shortly after D-Day, three replacement pilots were posted to B flt: Jock Ellis, Derek Lovell and Bob Farmiloe. Jock was a WO who had been flying Hurricanes on a Havoc/Hurricane Night Fighter Sqdn. Derek was also a WO who had been an instructor. Bob was an enigma as any reference to his past was tactfully ignored. He was a tall and well-spoken English Sgt pilot and those of us who had been playing at Boy Scouts for the last four months envied his tailored battle dress, silk cravat and ebony cigarette holder. Jock and I shared a tent or a room with Bob for almost a year and it gradually emerged that he had been a pre-war naval officer who had flown with the Fleet Air Arm and, in his own words, had been asked by the Lords of the Admiralty to resign! A few weeks after leaving the Navy he had received his call-up papers for the infantry but, with some help from friends in high places, had joined the RAF as a Sgt pilot. Because of his FAA record, he was posted almost immediately to 197 Sqdn.

From now on until the end of the war, the four of us were the backbone of B Flt, flying in excess of 500 sorties – mainly low-level attacks. Since the Squadron never switched to rockets, we must have been the most experienced bomb-dropping flight in 2nd TAF. The old hands would normally deliver their bombs well within a radius of ten to fifteen yards of the target including many direct hits. Consequently, we were employed mainly on special targets such as bridges, Army, Gestapo and SS headquarters, ammo dumps, ships etc. As this type of target was usually well-defended, they were called “Tit Shows”. Time has erased the memory of the majority of the sorties. Some remain, D-Day, the Falaise Gap (twenty-five sorties in less than three weeks, so many targets that you could hardly miss), the Seine Crossing, Channel and Dutch islands, a German HQ at Dordrecht and sinking the 22,000 ton SS Deutschland in Lubeck Bay (Byrne, Lovell & Farmiloe) on 3rd May 1945.

There are another two flights which stand out: At Needs Oar Point, the Sqdn was issued with an Auster a/c. I became the Auster pilot and would take people on leave or on official trips. When we were at Antwerp I was detailed on two occasions to fly two Reuters correspondents in the Auster to cover the landings on Suid Bederland and Flushing. This entailed flying along the beach at around 500ft so that the photographer could record the assault troops’ landing. After three or four low-level passes, the Jerries were most anti-social and opened fire with ack ack. It was time to call it a day and go home. The report and pictures were front-page news in the national press. Tongue-in-cheek, I enquired whether these trips counted as ops – you can guess the reply.

In early 1945, four aircraft from B Flt (Byrne, Lovell, Farmiloe and another) were on an armed recce in Northern Holland and were told by Control of a bandit due north. The chase began with full throttle and we slowly made ground on a twin-engined aircraft which, by the looks of the black smoke pouring from the engines, was going flat out. As we got closer, it turned out to be a Mosquito and, as the Typhoon is very similar to an FW 190, the Mossie pilot must have thought it was not his day with four 190s slowly closing in. Even when we were close enough to read the Sqdn code letters on the A/c, the pilot was not taking chances and was still flat out. It would have been interesting to have been a fly-on-the-wall during his debriefing.

During my time on 197 Sqdn, more than sixty pilots came and went. Almost half were KIA [killed in action] or POWs [prisoners of war], five or six were posted, tour expired, as they had survived from early 1943 and went on rest in the summer of 1944. Some did not come up to standard and went back to Aston Down or OUT. Some just departed after a week or two: no questions asked, no answers given – some on medical grounds and a few got the twitch. Four of my Flt Commanders were promoted (we trained them well in B Flight) and given their own squadrons. The old hands just carried on until the war ended.

How the pilots spent their leisure time is another story.

Flying Officer John Kilgour “Paddy” Byrne

Born: April 6, 1922, died: November 16, 2020